Daily tidings of impending ecological catastrophe make it hard to stay positive – but gardeners have can-do ways to mitigate the crisis.

Down one day, up the next. Gloom and doom gathers, before some light shines in. ‘Why bother?’ worms its way in, and then is cheerily ousted (usually) by a jolt of ‘Yes!’ can-do gardening resolve.

That’s just a typical week in the life of this aiming-to-be-earth-friendly gardening writer, who’s trying to make sense of a fast-changing, ecologically unhinging world, where bad news arrives daily by the wheelbarrow-load. November’s gloom tightened its grip only days ago when Insect Declines and Why They Matter, written by eco-communicator extraordinaire Professor Dave Goulson and published by the Somerset Wildlife Trust, arrived. Do read it, but keep some can-do grit handy. (It was Dave Goulson who, not that long ago, analysed some of the plants and bulbs flogged at the time as ‘perfect for pollinators’ by garden centres, and found them drenched in pesticides.)

It’s sobering stuff. Its doomy message is that the global abundance of insects – which, together with spiders, worms and others, make up the bulk of all animal life – has declined by 50% since 1970. Fifty per cent. That sure made a down day. The upside (the only one) was that I learned something. I didn’t know that the UK population of spotted flycatchers fell by 93% between 1967 and 2016, nightingales by 93%, grey partridges by 92% and cuckoos by 77%.

These declining species share one thing: they all eat insects for food. Butterflies are on the down, too; common species’ numbers dipped by 46% between 1976 and 2016. I didn’t know that the number of garden tiger moths (Arctia caja) – whose hairy black and orange caterpillars eat dandelions, and other stuff – crashed between 1968 and 2002, and that this is a factor in the rapid decline of cuckoos, who specialise in eating… big hairy caterpillars. Nor did I know (shame on me) that earwigs make fabulous parents, or that they gobble up aphids; in orchards, a thriving earwig population can dispose of as many aphids in a year as three rounds of insecticide.

Dave Goulson’s report socks it to us: ‘insects may be in a state of catastrophic collapse… if declines are not halted, terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems will collapse, with profound consequences for human wellbeing.’ Remember that when you next pass a shelf groaning with pesticides and weedkillers at your local garden retailer.

So what’s driving this insect apocalypse? The causes are interwoven and still debated, but boil down to habitat loss, exposure to cocktails of pesticides, fungicides and weedkillers, and climate breakdown, all hitting at once. There’s also compelling evidence that artificial light pollution is sending insects into a spin, making them more predator-prone, disrupting their mating patterns, or causing them to flutter themselves to death through exhaustion (this pollution is easy to tackle: just turn it off).

It’s gloomy stuff, but there’s a can-do clarion call. ‘We urgently need to stop all routine and unnecessary use of pesticides and start to build a Nature Recovery Network by creating more and better-connected, insect-friendly habitat in our gardens, towns, cities and countryside.’ The scale of the ask is huge – that’s why it’s a recovery network. But while others will doubtless need to debate a way forward, we gardeners don’t; we can beam some can-do light into our ecologically darkening days right now. My can-do just landed, with a thud, in a cardboard box; things are on the up.

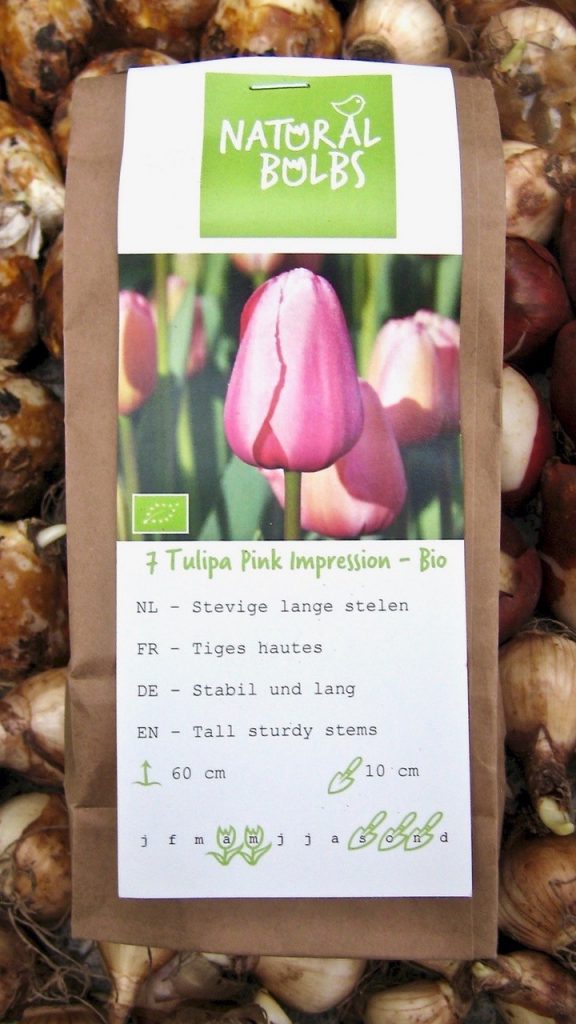

My evolving garden is still a relatively bulbless desert, because of my reluctance to buy bulbs other than those I know have been grown to organic standards. Most flower bulbs are factory-farmed and routinely treated with pesticides, fungicides and weedkillers. The insecticides used are often systemic: they’re absorbed into the tissues of the plant. When a polluted bulb blooms, that chemical – one designed to kill – flows to the flower, tainting its pollen and nectar, dealing a potentially fatal blow to any foraging bees or other insects – and to any birds that make a meal of them. I don’t want any part of that, no matter how tempting the packaging might be, or how cheap the bulbs are (they’re only cheap because our natural world pays the true cost of their production).

I’ve had much success with organic tulips and crocuses, but the range of organic bulbs is still limited (if not shrinking) in the UK, and when you do find them, they’re often grossly overpriced. My other option is to buy non-organic bulbs, almost certainly doused in pesticides, plant them, and then remember to mercilessly behead them before their first flowers open (this doesn’t work with tulips, because their best blooms are those that appear the spring after planting). The logic is that should they contain systemic pesticides, they’ll expel most of them in that first flush of flowers, so I can intercept it by chopping their heads off. It would still leave me with potentially polluted flower buds to dispose of; some pesticides, namely the neonicotinoids or ‘neonics’, are persistent and mobile in soil and water, so composting them is a conundrum. It’s an awful lot of faffing in order to add bulbs to my garden to bring me joy, while not poisoning our world’s embattled insects.

But my doom-busting, can-do box from Natural Bulbs, a Dutch supplier working with certified organic bulb growers, is totally faff-free. They’ve got an impressive range, from the familiar Narcissus ‘Tête-à-tête’ to the more exotic Camassia leichtlinii. I’ve got some dog’s tooth violets (Erythronium ‘Pagoda’) in the box, too, and Narcissus ‘Bridal Crown’, to pot into peat-free compost and nudge into life in my unheated greenhouse.

Because there are no poisons to worry about, I’ve also made an albeit tiny dent in mitigating climate breakdown; most pesticides are made from oil, which requires energy, which releases carbon dioxide. Oh, and there’s no plastic in the box; all the bulbs are in paper bags – which, along with the cardboard, will become worm fodder and then soil food. It’s also reassuring to know that the land they came from is being nurtured with respect. The little pack of free species tulips ‘to give to a friend’, and the smiley face hand-drawn on the slip, are nice touches.

Doom be gone. Go away gloom. By planting these nature-friendly bulbs, I’m upgrading my own garden’s insect-friendly connection to that vital Nature Recovery Network. It’s one tiny node, but it’s one of millions, connecting gardens and allotments, urban and rural, across our challenged land. We can all do this, and we can do it now. Yes!

Text and images © John Walker

Find John on Twitter @earthFgardener