Gardeners love a September day, when morning mist and heavy dew give way to warm afternoon sunshine. It’s more than that though: the garden is bathed in a crystal clear light that flatters colour and there’s a relaxed air. No need to rush, the garden’s winding down and so am I. I always liken early autumn to a heavily jewelled, decadent woman who’s seen better days but hasn’t given up on life – yet! She’s still putting on the lippie and bling.

It’s not a bad analogy, for there is an inescapable air of shabbiness as summer fades. Herbaceous peonies have been heading towards dormancy since August, although they will be among the first to poke their red spears above the ground next year so I forgive for this. Many annuals have finished for the year and been consigned to the compost heap. Touches of brown, whether dried leaf, stem or seed head, are beginning to run through the garden like a series of rusty nails – announcing the demise of summer nail by nail. The colour palette is morphing into khaki, brown and black and rightly so, for winter is not too far away.

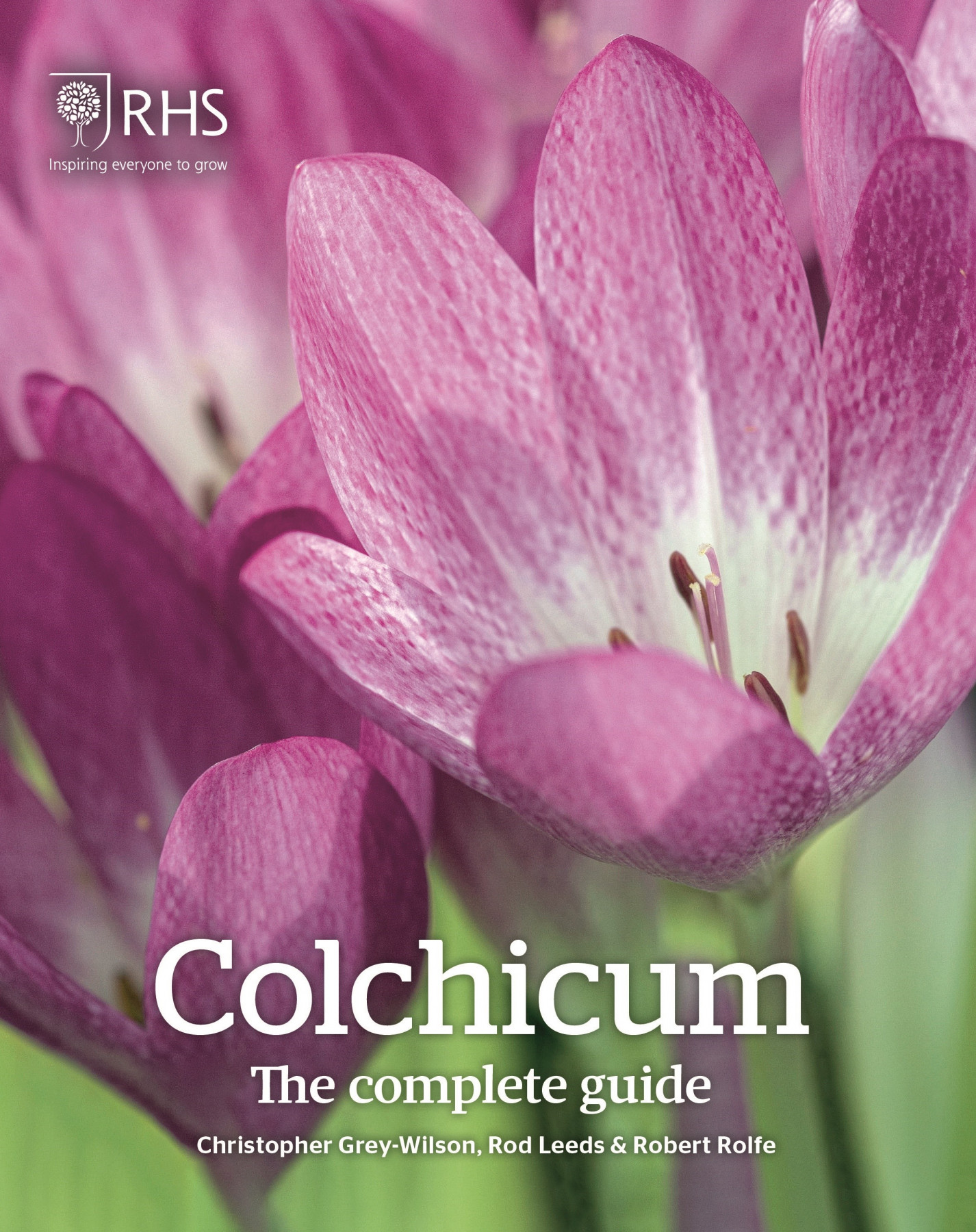

It’s one of the reasons I admire those fresh bursts of September flower and they’ve been particularly good this year, following a warm, wet winter and a glorious spring. My autumn crocuses, or colchicums, are swooning on garden edges and round fruit trees, in shades of pink, wine and pristine white, like flushed drinkers who’ve had one too many. Their common name, naked ladies, says it all for their goblets push through damp ground several months after the leaves have faded. Flowers without leaves are beguiling and I can’t get enough of them. This is the first year I haven’t added more to the garden, because of lock down.

The gardener has to site them carefully, for these Jekyll and Hyde characters often produce ugly foliage early in the year. Although toxic, colchicum foliage attracts snails even in its faded state. The upright sheath of leaves die badly and turn tobacco-brown by early summer and then flop horribly. I hide mine round fruit trees and on the far edges of an autumn border, places where they don’t jar the eye. Others are tucked away waiting for their moment of glory. The other option is grow them with hardy geraniums, ajugas or ferns, so that the foliage is hidden by their associates.

Colchicum foliage varies greatly and there are two readily available ones that produce much less obtrusive leaves. Colchicum autumnale ‘Nancy Lindsay’ is named for an upper crust lady, the daughter of Norah Lindsay. Nancy (1896-1973) collected plants in Western Asia between 1935 and 1949, principally from Iran. This was the era when collecting plants in the wild wasn’t frowned upon. It is now! Many of the bulbs we’ve enjoyed for decades were simply dug up by wealthy gardeners who were on rather up-market plant hunting expeditions. A note of jealousy is creeping in!

An excellent new RHS book, Colchicums – the Complete Guide by Christopher Grey-Wilson, Rod Leeds and Robert Rolfe, tells us the Nancy probably collected her colchicum in Romania in 1936, on the way back from Iran. The flowers consist of small deep-pink champagne flutes with strong necks, the type that hold in the fizz, and one bulb can deliver up to 20 sanguine blooms from August onwards.

C. autumnale is also found in damp west country pastures in Britain so it’s easily grown in gardens and will thrive in damper places. I have to place Colchicum x agrippinum far more carefully because it hates being waterlogged. The August flowers appear before my others and they open widely to display heavily tessellated patterns. I have lost this treasure in cold winters, so find it a warm dry spot.

Luckily most of my colchicums don’t mind it damp and mine rub shoulders with another South African native Hesperantha, although you might know it by its old name of Schizostylis coccinea. These are commonly called Kaffir lilies and they thrive in warmth and high rainfall on river edges and on damp cliffs. We get the high rainfall in Cold Aston, but not the warmth, so my hesperanthas are never huge affairs.

Recently I visited a Welsh NGS garden south of Usk, Highfields Farm owned by Roger and Jenny Lloyd. Their Kaffir lilies had formed enormous clumps, just as they do at a nearby garden called LLanover. Although mine are tiddlers by comparison, each flowering spike will produce a dozen or so saucers and they lean over slightly and match the relaxed, mellow mood of autumn. ‘Major’ is a tomato-red, but I prefer ‘Pink Princess’ because it mingles among the colchicums without jarring the eye.

By mid-September my colchicums and Kaffir lilies have been joined by nerines against the south-facing wall of the house. Every shade of pink from Barbara Cartland to Doris Day is represented here and they don’t all flower at once. Nerine bowdenii is hardy in gardens, but like most bulbs it needs good drainage. This year there are 75 flowering stems, the best yet!

Nerine bowdenii is from the Eastern Cape of South Africa and the species was named after Mr Athelstan Cornish-Bowden – a name to conjure with. He sent bulbs from the King’s William Town area of the Eastern Cape to his mother in Devon in the early 1900s. Once the Dutch bulb growers knew where these lovely flowers were, trainloads of bulbs were lifted and as a result this bulb is rarely found in its native land. That explains the importance of modern-day restrictions on plant hunting, it’s an attempt to avoid rape and pillage.

You could also grow greenhouse nerines labelled N. sarniensis in your Hartley greenhouse. These Guernsey lilies have larger flowers in shot-silk colours that have iridescent touches of blue. I have two dozen potted up Guernsey lilies and they do best when left to their own devices. They don’t all flower every year, but they do provide flowers late into the year and these pick well, although I can’t do it. Not everyone will flower very year, but the cardinal-red ‘Wolsey’ and the duller red N. fothergilli ‘Major’ are my most consistent flowerers. I acquired this through the The Nerine and Amaryllid Society, a very friendly plant society well worth joining, have bulb exchanges and sales. www.nerineandamaryllidsociety.co.uk

The last flowers standing are always hardy chrysanthemums, which have had something of a revival due to the cut flower ladies. These should not be confused with greenhouse-grown ‘mums’. These are late and hardy, in good drainage, and many of them have been grown in gardens for over eighty years or so. ‘The single pink ‘Clara Curtis’, launched by Amos Perry in 1939, is the perfect partner for pink nerines, because both peak in September.

One of my favourite hardy chrysanthemums bears the name ‘Emperor of China’, although no one is certain if it has a Chinese provenance. The dusky-pink flowers have quilled petals and the foliage darkens to plum. It’s one of most perennial chrysanthemums and it used to be known as ‘Old Cottage Pink’, because these hardy chrysanthemums were 19th century cottage garden favourites.

The late Christopher Lloyd advised his readers to remove the lower leaves, bash the stems and give them a long drink before arranging them. Personally, I can’t bear to pick them. I let them catch the spiders’ webs instead!