Real gardeners go out whenever they can and, at this time of year, there’s a lot to do. I’ve been busy, very busy, because it’s been dry and cold rather than wet and warm. Several white dumpy bags full of leaves, testament to my efforts, are discretely tucked away on the far side of my new Hartley greenhouse. And, there are still plenty of the blighters to pick up. My shoulder’s sore and my back aches, but this tedious job has to be done at Spring Cottage.

You see we have the wrong kind of leaves, as British Rail would say, because they are mostly beech leaves. These leathery, lignin-packed leaves take longer to rot down than most other leaves do! If I leave them to it, they form a thick soggy layer and water gets trapped underneath. That encourages little black slugs and they nibble the trilliums and snowdrops lurking in my woodland patch. So up they come!

Not all leaves are so troublesome. If they were hazel leaves, for instance, I could leave them alone because they form a drier, lighter layer. Snowdrops love pushing up through hazel leaves. So gathering and raking beech leaves is a daily occurrence and they will used to make leaf litter, the black gold of gardening. This crumbly, slow-release mulch is applied to the woodland patch and the plants love it.

Sounds easy, but there’s a glitch. The leaf litter made from previous year’s gatherings can’t be applied until this year’s leaves have been collected, because it has to go on bare ground. Currently I have one full leaf bin, hopefully containing some magical black gold further down, and lots of this year’s leaves in bags. It’s a logistical leaf jam and it’s one that can only be sorted out in clement conditions. Freezing weather makes leaf litter stick together and I like to sieve the beech nuts out. There’s another problem. If you apply it to frozen ground, it traps the cold into the soil and slows up the growth of bulbs and woodlanders.

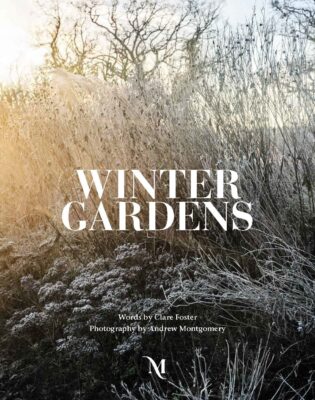

It will take time to clear my logistical leaf jam, but winter allows for time. The garden is hibernating for a few weeks, before the rush and tumble of spring kicks in again. There is a new book, published earlier this year, Winter Gardens, with words by Clare Foster and pictures by Andrew Montgomery. Gardeners, driven in by darker nights, have time to read and look at pictures. It will inspire you in one way and make you grateful for a warm room in another way. It’s a perfect way to spend a winter afternoon.

It’s still early December, so it’s early on in the winter timeline, but there are already compensations to be had. The winter jasmine, Jasminium nudiflorum, has some bright yellow starry flowers on its green stems and they pick very well. ‘Freckles’, a winter-flowering clematis, is producing pendant lamps of putty-coloured silk highly spotted inside in bright-red. There’s a little bit of bloom of Viburnum x bodnantense ‘Dawn’ too, giving off a smidgeon of hyacinth scent. Real flowers are few and far between, though.

That’s why I find delight, when I move a thick handful of leaves and uncover some thick points of snowdrop bulbs pushing upwards. If the points are showing now, the flowers can’t be far behind. Or can they? There are handfuls of snuff-brown buds on the witch hazels and these will break early next year and produce marmalade shreds that look good enough to eat. But please don’t. There are pointed torpedo buds on the cherries too, ready and loaded, and these all speak of better days to come.

However, it’s the evergreens that really grab me on a bleak early winter’s day when the nights are still drawing in. These winter warmers glow at this time of year and they keep the garden alive and make you feel that the garden’s pulse is in good heart. It’s no wonder that our pagan ancestors revered The Green Man, thinking that he brought life back again in the spring. The Christian church adopted the symbolism and many a Medieval cathedral, including Norwich, St Albans, Lincoln, Canterbury, Gloucester and York, has a Green Man gazing or two. Inevitably, the Green Man became associated with the Resurrection.

Oak leaves normally surround the Green Man and this is one of the last trees to shed its leaves. It is the acknowledged King of the Forest, but I haven’t got enough room for a mighty oak tree. English oak, Quercus robur, is a majestic tree and the jay, a colourful member of the crow family with a blaze of blue on its wing, is never far away. He, or she, collects and buries the acorns in the filed by my house.

I do have room for a plant that’s associated with the majestic English oak, the holly tree. This sacred plant was revered by the Druids and they are said to have made crowns for their heads. When Christianity came it was embraced as the crown of thorns. There’s a clue in the name of Ilex aquifolium, for aquila is Latin for eagle. The needle-like tips of the leaves make our native holly difficult to accommodate in a border, as I can testify. As a young gardener, I used it and bore the scars every time I weeded. Hollies, like most evergreens, shed leaves throughout the year so there are always some on the ground.

Holly could be accommodated in a border of winter foliage, one that you didn’t have to weed very often and it can be shaped and cut. One of the best places to see topiarised holly is at English Heritages’ Brodsworth Hall near Doncaster in Yorkshire. Spires, cones and spirals of holly and other evergreens make this a great garden to visit in wintertime. Clipped holly doesn’t berry, because you’re cutting off the flowers every year, but it can look very chic in winter light.

Hollies are either make or female, because the flowers are borne on separate trees. Pollen has to be transferred from male to female flowers, before the berries form. Many gardeners use New York holly, Ilex x meserveae ‘Blue Prince as a male pollen source, because it’s relatively compact. It’s said to service a harem of ladies. If you’re in a built-up area with lots of gardens, there will probably be male hollies close by.

There are some impressive female hollies, forms of Ilex aquifolium, that develop a natural shape and berry. Many also have variegated foliage. ’Argentea Marginata’ is an 18th century variety with high-gloss green leaves edged in yellow and plenty of bright-red clusters of berries. ‘Handsworth New Silver’ (1850) has narrower leaves (to my eye) and the green is more mottled and the edging creamier. I do not like the self-sterile ‘J.C. van Tol’ because the berries develop along the stems. It is favoured by florists, especially for wreath making, because it has smoother stems and almost spineless leaves.

If you want to have a more finger-friendly holly there’s a handsome, hybrid holly that originally arose at Highclere Castle, Ilex x altaclerensis. These are known as the Highclere hollies and they have rounder foliage and larger berries. These are used in hedges, because they’re faster growing, but they can be shaped into lollipops. I interviewed the Head Gardener of Highclere Castle many years ago. He told me that an exotic, tender holly from the Canary Islands, Ilex perado, had been grown in the Orangery to provide extra greenery. The citrus trees and hollies at Highclere Castle were moved outside in summer and it’s thought that pollen from this tender holly was carried to the female flowers of our native holly growing wild in Highclere’s woods. Rounder-leafed seedlings followed.

These vigorous hybrids, which were first identified and named at Highclere in the 1870s, were then found growing in other places, because I. perado had been introduced in 1760. One of the best, ‘Golden King’ has a misleading name because it’s actually a female berrier. The oval foliage has a dark-green middle, splashed in grey-green, and the broad, irregular margin is creamy yellow. This is the best one to clip and shape, because the growth habit is denser.

‘Lawsoniana’ is brighter because the central part of the leaf is splashed with yellow flecked and edged in lighter green. There are some rules about variegation. Firstly, use it sparingly among all-green foliage. Secondly, be aware that cream or white and green is cooler in tone than yellow and green. I feel, they don’t mix together well. Lastly, cut off any green shoots you see, because variegated plants have a tendency to revert to green.

If I had a massive garden, rather than my third of an acre, I’d plant the pyramidal I. aquifolium ‘Argentea Marginata’. It’s spiny and free-fruiting, although the birds would strip it before Christmas.