The most experienced of gardeners can be bested by vine weevils – but calling in a microscopic earth-friendly ally will settle the score.

Otiorhynchus sulcatus got me in the end. After 17 years of mostly grub-free bliss, when I’ve relied largely – apart from the occasional gentle shove – on nature (and some wire mesh) to keep my greenhouse and garden plants safe from nibblers, notchers, peckers, gobblers, sap-suckers and munchers, my potted and much-pampered strawberries have finally fallen victim to what even the most assiduous organic and earth-friendly gardener lives in trepidation of: vine weevil.

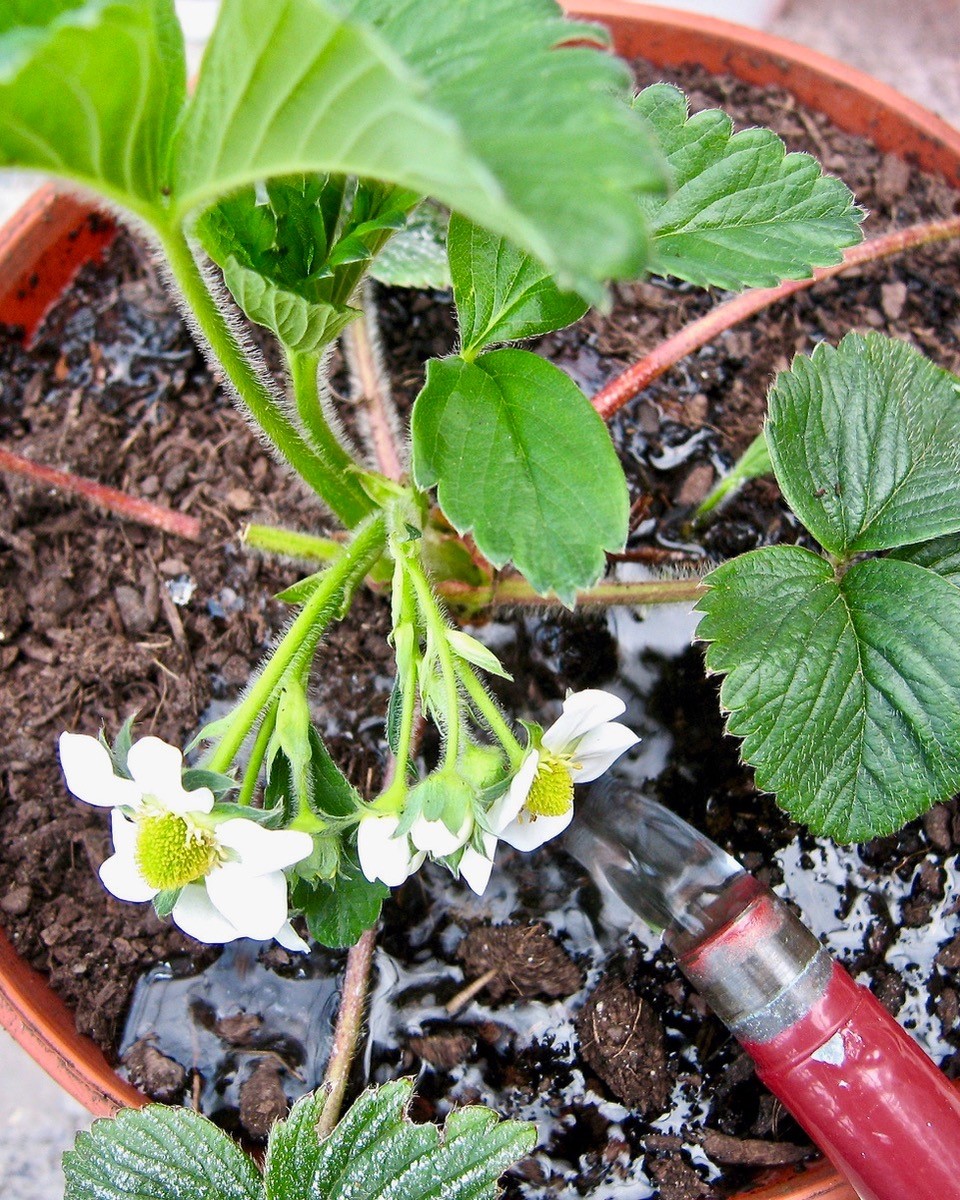

I knew trouble was afoot when the crowns of several plants were sluggish to leaf up, as March’s rays warmed their pots. My plants spend winter outside before coming into my sun-powered lean-to in early spring, when they’re repotted, and then gently coaxed into flower. They fruit here, too, away from gobbling squirrels and pecking blackbirds, from early summer onwards.

As some sprouted new, bright green leaves, others sat dull and lifeless, which I casually ascribed to old age – some are five-year-old veterans, with thick and woody crowns. But when repotting time arrived, it was a grim moment when one of those listless crowns parted company with the now non-existent roots in the compost below; toupee-like, it just lifted away. Then the crushing blow: the centimetre-long, C-shaped, cream-coloured, hairy, shiny-brown-headed and wriggling larvae of Otiorhynchus sulcatus were revealed, in all their gardener-toppling glory.

Not just one, mind, but a legion – well, it seemed that way at the time – of them, which had spent months quietly hidden, chewing the roots of my treasured strawberries into rust-coloured frass; I found several grubs nestled deep in the woody crown. To add perplexity to injury, I’d never actually seen an adult vine weevil in my greenhouse (or anywhere else), nor spotted the tell-tale notches the adult beetles chew from the edges of evergreens such as rhododendrons (they cause minimal harm) – and my patch is several hundred metres from neighbouring gardens. Centimetre-long adult vine weevils don’t fly, but laggardly crawl and climb.

What adult weevils do do is live for up to three years, and they can lay hundreds if not thousands of tiny, millimetre-wide brown eggs in pots of compost, and in garden soil, through spring and summer; a single adult can lay waste to several plants (or annihilate a single specimen confined to a pot). For such a fecund beetle, it stung to learn that Otiorhynchus doesn’t even need sex to proliferate: all adult weevils are female. You’re unlikely to spot their eggs – the pale brown (or green or blue) orbs you might find among the compost of plants bought from a garden centre are just long-lasting fertiliser granules. White granules are bits of perlite, and any shiny shards are vermiculite.

Weevil hatchlings feast first on fragments of organic matter, then on root hairs, then on thicker roots, and then – the killer blow that can finish even woody plants off – the crowns and bases of plant stems. No wonder some of my strawberries looked so wan; the grubs had devoured all of their roots, save a few threads allowing them to cling to life, and were nibbling into the faltering crowns. The hidden onslaught began sometime last spring or summer and, unseen, the shiny-headed critters have been growing ever plumper through autumn and winter. Their feeding frenzy reached its zenith in recent weeks, just as the afflicted plants threw their all into a burst of new growth, before wilting and faltering and dying in the spring sun. If I’d delayed repotting any longer (and I toyed with skipping it this year), many of the shiny-heads would have morphed, still unseen, into pupae, emerging as adults, creeping from the pots under cover of night (they hide during daylight hours) to lay the seeds of more silent carnage.

Once I’d lifted the first rootless toupee from its pot, and recovered from the shock, I entered salvage mode. Not all of the strawberries were goners. The runners I’d rooted last summer had pots filling with roots, and were repotted. Any old-timers sprouting strong new leaves and clusters of fattening flower buds were knocked from their pots for a thorough check-over.

Prising the old compost from their wiry, reddish roots, it was soon obvious if Otiorhynchus had struck. Those with only a few grubs in the pot and with otherwise sound, pale and actively growing roots were repotted in fresh peat-free compost (SylvaGrow Organic). I didn’t remove all of the old compost, just enough to assess whether the plant was likely to be a survivor.

Any ‘toupee’ plants, whose roots were completely gone, or where the remains were brown and lifeless, and where grubs tumbled out by the dozen – or were actually embedded among pockets of rusty frass in the plant’s besieged crown – were ditched. Tempting though it was to peevishly squish the shiny-heads, I took them (together with all of the old compost) to a more fitting fate, up into the wood, laying them out on the altar of the local robins.

Vine weevil does have its garden-found nemeses: birds, frogs and toads, hedgehogs, shrews, and ground and rove beetles are all devourers of both adults and grubs. But although they might help to curtail this elusive assassin in your borders, I can’t see a hedgehog (even if I had one) cutting it as root guardian to my potted strawberries. So I’m turning to a tried and tested solution that’s six million strong, which has just arrived by post, and is as natural as it comes.

The pack of damp, cream-coloured powder I’m about to mix with water contains six million insect-pathogenic and naturally occurring nematodes – tiny microscopic worms, Steinernema kraussei, which are bulked up in large vats; a basic pack costs around a tenner. After being watered onto my potted strawberries (in the cool of the evening; use a coarse rose, or leave it off altogether), they’ll seek out any overlooked grubs and, when they find them, invade the shiny-heads and release a fatal, natural bacterium that does them in. Inside the grubs’ browning carcasses, the micro-worms proliferate, before spreading throughout the pot in search of more grubs.

Nematodes can also be used outdoors on weevil-afflicted plants/areas (preferably during good soaking rain), and on outdoor potted plants; they’re a completely safe-anywhere-in-the-garden, chemical-free, non-polluting solution. They’ll be grub-hunting from the get-go in the warm, moist compost in my strawberry pots, curtailing the current round of fatal nibbling that’s caught me on the gardening hop.

The downside is that I will – bar a miracle – now be hooked on regular fixes of these microscopic allies; once you’ve got vine weevil, you’ve got it for life. I don’t doubt that the blasted beetle is now lurking elsewhere in the garden, and I’ll never track them all down. So my treasured strawberries will need another Steinernema hit come autumn, to zap any shiny-headed grubs hatching from summer-laid eggs. Then, next spring, I’ll do it all over again.

Sending six million allies into battle felt like the last weevil-banishing laugh. But when an adult Otiorhynchus strutted down the inside of my kitchen window the day after, I knew I was beat. Resisting the desire to squish (stamp, even), I did the only thing I could: I took her to join her kin on the robins’ altar.

Text and images © John Walker

Find John on Twitter @earthFgardener