Now a firm part of British culture, over the last few centuries, the great English Victorian Glasshouse has become an iconic feature in botanic gardens throughout the country. Often thought of as a cornerstone of gardening itself, the history of the English glasshouse takes its roots from far and wide.

Early beginnings

Although a far stretch from the glasshouses that we know and love today, the father of the early glasshouse is often cited as Emperor Tiberius, the successor and stepson of Augustus, founder of the Roman Empire.

In and around 30AD – a mere seven years before his demise – royal physicians, concerned over the health of the ailing emperor, prescribed him to eat one cucumber-like vegetable a day. As the plant grew only in the heat of summer, a solution was required to bolster its chances of survival throughout the rest of the year.

Searching for a new way to grow the plant, his skilled gardeners developed artificial growing carts set on wheels, covering the vegetables with an opaque-like plastic. This enabled the plants to grow with the perfect amount of heat and light throughout the year.

Thomas Hill, in his book The Gardener’s Labyrinth (1577), wrote:

“The young plants may be defended from cold and boisterous windes, yea, frosts, the cold aire, and hot Sunne, if Glasses made for the onely purpose, be set over them, which on such wise bestowed on the beds, yeelded in a manner to Tiberius Caesar, Cucumbers all the year, in which he took great delight…”

According to Pliny the Elder, once the means of growing were firmly established, “he was never without.”

Italian and Korean Development

Ancient roots aside, significant advances in glasshouse development were also had later in Italy, where around the 13th century, the first botanic gardens (Giardini botanici) were developed to house tropical plants and vegetables taken from around the world for medical research. The two earliest botanic gardens were found at the Vatican and Salerno – though sadly, neither exist today.

Around this period the term ‘Holy Roman Empire’ began to grow common, although it is likely that the gardens would have been used for plants taken from other parts within the empire itself, as by this time, the reach of Roman influence had shrivelled to Germany, Burgundy and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

It is thought therefore, that any exotic plants grown within the gardens would have been brought by early explorers and tradesmen, who would have scoured the lands far and wide in return for rich rewards.

Around circa 1450, significant glasshouse development occurred across the globe in countries like Korea, where fully ‘active’ (temperature controlled) houses were being built, as written by Jeon Son in his 1459 cook book, Sanga Yorok.

Another reference occurs in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, which describes mandarin trees being grown in a traditional Korean glasshouse in the winter of 1438. According to the records, an Ondol heating system was used to raise the temperature of the glasshouse during the cold winter months.

Active glasshouses would not yet appear in Europe for nearly 300 years.

THE HISTORY OF FRUIT, VEGETABLES AND GLASSHOUSES

Throughout the history of greenhouses, it has always been a goal of many to grow fruit and vegetables from different climates. By doing this, people have had the opportunity over time to experience new culinary delights from around the world.

In the beginning, oranges were a popular growing choice, specifically under the reign of Elizabeth the first. This was due to their impressive flavour and decorative appearance.

As time went on, the famous South American pineapple fruit and grapes from the Mediterranean entered greenhouses. Glazed roofs were created so there was a good amount of light exposure and that high temperatures could be reached to provide the correct growing conditions for the fruit.

The pineapple became known as one of the most exotic fruits in the UK and took centre position on a Georgian dining table as a signature dessert.

Glasshouse innovation continued, with the introduction of palm and tropic houses, which we recognise today as grand glasshouses.

One of the most famous British glasshouses from the past is Orchard House, which dates back to the 1870s. It has three large sections which contain the following:

- Section one: Figs and grapes

- Section two (middle): Pears, grapes, apricots, lemons, oranges, mandarins and more.

- Section three: Peaches and nectarines

The glasshouse was created to shelter the trees inside, and each pot inside is designed to rotate so the entire plant can be exposed to the sun.

European and English popularity

Thanks to Italian influence, glasshouses began being built in both the Netherlands and England throughout the 16th century, although the first glasshouses in Britain came in the form of orangeries; often built to shelter citrus fruits imported from Spain.

Like their early Korean counterparts, the early English orangeries utilised underfloor heating via charcoal, although later designs made use of hypocausts– a Roman invention dating back from 1st century BCE.

It is thought that orangeries became popular when William III, Prince of Orange and stadholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht Gelderland and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic, became King of England, Ireland and Scotland in 1689.

Throughout the 17th century experimentation began on a grand scale, as technological advancement meant that better quality glass and metal could be produced to aid construction methods.

It is often thought that the first truly practical glasshouse was built by French biologist, Charles Lucien Bonaparte (nephew of Emperor Napoleon) in Holland. Like the earlier botanist gardens in Italy, Bonaparte would use them to store tropical plants for medicinal research and use.

Around the same period, the glasshouse at the Palace of Versailles was also built, after being commissioned in 1661 by Louis XIV. Upon completion, the great house would measure 490 ft long, 43 ft wide and 46 ft high.

It could be said that the building of the great glasshouse marked a new period in time; one where glasshouses were truly the must-have toys of the aristocracy and social elite – as before this they were owned only by a handful of universities, governments and scientific institutions.

But all that was about to change.

The dawn of the English Glasshouse

Thanks to the hefty window tax introduced in 1696, and the glass tax introduced in 1746, glasshouses in Britain at this time were afforded only by those who enjoyed extreme wealth. Indeed, a large glasshouse of the 18th century signified prestige, wealth and power – a little like the Ferraris and Lamborghinis that stalk the roads of Kensington and Chelsea today.

This however, only worked to fire the imaginations of the working classes, who could only stand and watch as these giant glass buildings sprang up throughout the land.

So cutting edge were these buildings that one glasshouse at Wentworth Castle in Yorkshire was to have electricity installed even before Buckingham Palace itself.

According to Fiona Grant, writing for The telegraph:

“As the craze for glasshouses flourished, increasingly innovative structures were designed, to maximise light and create the perfect temperature for the plants inside.

“Ventilation was created by adding sliding frames at the top of the roof, while roofs were made of glass angled to catch the sun.”

The appetite for botanical status continued throughout the 19th century, but it wasn’t to last. During the Industrial Revolution, the cost of making glass dropped dramatically, and furthermore, both the glass and window taxes were abolished; making glasshouses affordable to a greater percentage of the population.

It wasn’t long before glasshouse manufacturers realised that there was also another market outside of the finite super rich – the more populous middle classes.

By the early 20th century, as the world slowly crept out of the “golden” Victorian era, plain, self-assembled and small glasshouses were manufactured, so that those with enough space and money could afford their own glass and iron structure within their very own garden.

But regardless of size, glasshouse innovation continued.

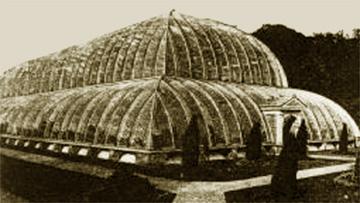

Larger winter gardens began being built for those who wished to grow out of season plants. Unlike before, these would come built against or directly attached to the main property. A design feature that would become more popular was the introduction of the geodesic dome; the primary design principle behind the Eden Project in Cornwall, and The Climatron at the Missouri Botanical Garden in the United States.

Throughout the 1960s, glasshouse structures evolved still, when glass found itself replaced with polyethylene film. Otherwise known as greenhouses and hoophouses, the structures became a craze amongst avid gardeners and people who still couldn’t afford the pricier option of a full glasshouse.

THE CHANGE IN GLASSHOUSE ARCHITECTURE

As mentioned, the structure of the glasshouse has been one of constant evolution, not only with materials, but the shape and size too.

By the middle of the 19th century, the greenhouse became more than just a garden structure, and developed to a place where the environment could be controlled.

Greenhouse architects have created a huge variety of designs, from the impressive Temperate House at Kew Gardens to the contrasting design of the Pyramid-shaped Muttart Conservatory in Alberta.

What is a Glasshouse?

As the history and culture of the glasshouse is so layered, deep and at times complex, it is important to be able to identify the unique differences between glasshouses, orangeries, alpine houses, and of course, greenhouses.

A Glasshouse

The difference between a greenhouse and a glasshouse has led to many debates over the years, and although ‘greenhouse’ is a relatively recent term, the truth is that both words are synonymous of each other.

As nouns however, a glasshouse is often considered to be a building made of glass, where plants are grown more rapidly and conveniently than outside. A greenhouse also tends to be referred to as a building that is traditionally made of glass, but over time this has changed so it is now largely referred to as a building made from wood and polyethylene.

An Orangery

Originally, orangeries were built as extensions on large buildings, but as fashions changed, it soon became popular to have them separated from the main property. Often, they would be designed to imitate Greek or Roman temples, and built in the serene gardens of stately homes.

Although similar to a glasshouse or conservatory, the name of such a building reflects their original purpose, which was to protect citrus trees that would be raised in tubs and introduced into the building during early autumn. Later on, pineapples, shrubs and other such exotic plants would be introduced into the buildings.

The earliest surviving orangery can be found at Kensington Palace (see above), built in 1971 by Sir William Chambers. At one point it was the largest orangery in England.

An Alpine House

Something slightly more niche, an alpine house is a specialised glasshouse that is used especially for growing alpine plants. The purpose of an alpine house is to mimic the exact conditions of the alpine mountains – especially from wet conditions in winter.

Due to their nature, alpine houses are often unheated and are designed to offer plants superb levels of ventilation.

Winterhouses and Gardens

For an extended period of time, winter houses and gardens were popular amongst larger houses and were often attached to the main property. These attachments (very similar to the conservatories of today), enabled people to take exercise in all weather conditions.

What are Glasshouses built from?

As we’ve already seen, throughout history and across the world, glasshouses have changed dramatically from their humbled beginnings in Tiberius’ garden. But what, in all their forms and variants, were they largely constructed from?

From around the 13th century, glasshouses were generally built from the same few materials, until around the Victorian era, when both cast and wrought iron were introduced. Before this time, most glasshouses used frames built from both wood and metal.

Thanks to advances brought on by the industrial revolution however, both cast and wrought iron became readily available and eventually, wooden frames were slowly dissolved from construction.

Despite this however, there were some advantages to combining the two materials. For example, iron truss brackets and iron ties enabled architects to use shallower sections of timber. In addition to this, small sections of wood were found to be far more durable than larger sections in the more humid and deeper sections of the structure.

Before long, the increased use of iron helped drive manufacturing prices down, and cheap yet well-made glasshouses could be sold to the general public.

Interestingly, some of the more prestigious glasshouse designers distinctly disliked iron as a building material, believing it to be both costly and damaging to the insulation and glass. One prime example of this train of thought comes from Joseph Paxton, who thought that wooden structures could let in just as much light as iron.

To prove his point, he created a number of wooden glasshouses at the Chatsworth in Derbyshire. One of them, the Great Stove Conservatory, took over nearly three quarters of an acre and was even visited by Queen Victoria herself.

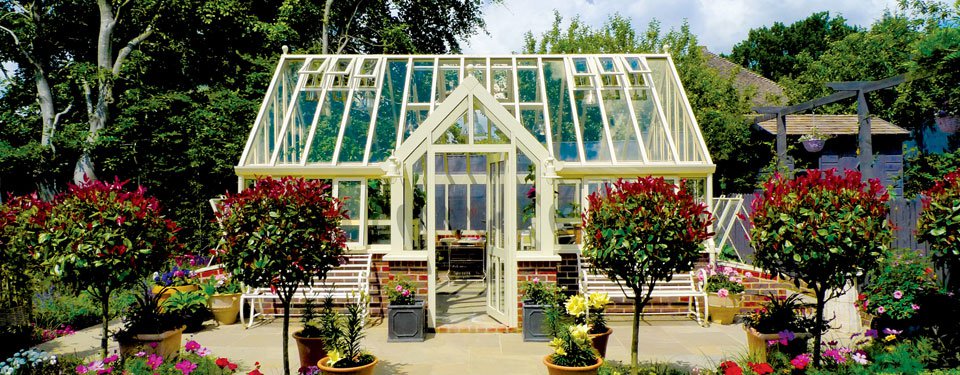

Today, glasshouses are made with the finest and most trusted materials available – mainly aluminium, which features throughout our most loved glass and greenhouses. Both lightweight and sturdy, and unlike iron, aluminium does not rust, which is why all Hartley Botanic products stand the test of time.

DESIGNS ARE SUITED TO PEOPLE

Although there is a huge selection of greenhouse sizes and designs out there nowadays, at Hartley Botanic, our designs are suited to peoples individual requirements.

Whether you’re searching for a greenhouse, that takes a prime position in your garden, such as grand Victorian-style greenhouse, or for a smaller, more subtle greenhouse as part of a growing hobby. One of the most impressive things about the greenhouse is that the designs can be altered for whatever you need.

THE FUTURE OF GREENHOUSES

Greenhouses have progressed throughout time, and in the future, they are sure to progress even further.

Every year, garden enthusiasts in the UK and around the globe, are creating new methods to enhance their greenhouse and gardening experiences.

One up and coming trend is greenhouse vertical farming, which is when crops are grown in a stacked style indoors, under artificial light and without soil. Although vertical farming seems to have a positive future, there are many perceptions that it cannot match the taste of produce naturally grown with soil and sunlight.

Another estimation for the future of greenhouses is that they will become more sophisticated with technology. For example, solar panels will mean greenhouses can become more energy independent and increase productivity. Another example would be the introduction of hydroponic greenhouse systems which can maximise space and conserve water.

Gardening and greenhouse styles are completely subject to individual requirements and tastes, but here at Hartley Botanic, we have a large range of greenhouses and can work with you to find a greenhouse that suits you.

View the full range of hartley products